Most every adult in southern Nevada is knowledgeable of Lake Mead National Recreation Area, Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, and Mount Charleston (i.e., Spring Mountains National Recreation Area), and has likely visited at least one, and probably all of three within their lifetime. As a young adult in the 1970s and 1980s I could find solitude by hiking just a mile or two in all these national treasures, but not today. Today the Red Rock Canyon trails feel crowded no matter which trail you take, and at its southern end the mountain bike trails have all but decimated any semblance of adventure while hiking to the lesser known springs and petroglyphs of Red Rock. The youngsters of today have no knowledge of what it was like 45 years ago when the valley’s population was 300 thousand residents compared to the 2.3 million here today. Back then, if one-percent of the population visited these areas on a weekend that would be 3,000 adventurists scattered in the hills. Today that would be 23,000 people, or almost eight times as many people.

For example, in its most popular seasons when valley residents are either running from the blistering Las Vegas summer heat or running to play in the winter snow of Kyle and Lee Canyons, if you are not one of the firsts into the Spring Mountains National Recreation Area you will not find a place to park your car anywhere on the mountain. It is ridiculously crowded. But today I can give you hope, because there is one national treasure which, by its very nature, can still be enjoyed in solitude.

Within twenty minutes from my home in the northwest part of Las Vegas I can arrive at the Corn Creek Field Station, the gateway into the Desert National Wildlife Refuge (DNWR). Other than around the Corn Creek Field Station, the DNWR can only be accessed by foot, horseback, or street-legal vehicles that must stay on unimproved dirt roads (that’s right, all-terrain vehicles and dirt bikes are not allowed in the DNWR). When I say unimproved dirt roads, I mean that high-clearance, four-wheel drive vehicles are recommended; “Travel at Your Own Risk” signs are strategically posted throughout.

My son Brian and I share an interest in four-wheeling as a way of exploration. For a few years we have discussed “wheeling” together on the Mormon Well Road through the DNWR. Today we did something about that.

The DNWR is the largest NWR in the lower 48 states. It covers over 2,300 square miles, which is twice the size of the state of Rhode Island. It was created in 1936 for the “protection, enhancement, and maintenance” of the desert bighorn sheep (a.k.a., Nelson’s bighorn sheep). The federal government purchased the Corn Creek Ranch in 1939 adding it to the DNWR. Corn Creek was surrounded by several springs, and beside cattle ranching it was also a stagecoach stop used by prospectors and cattlemen, and the occasional poacher and bootlegger. Today it boasts a very nice visitor center which I recommend.

The DNWR’s most prominent feature is the Sheep Mountain Range which runs almost 5o miles from the Corn Creek Field Office to the southern boundary of the Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuge (immediately south of Alamo in Lincoln County, NV). Its lowest elevation in the Mojave Desert is about 3,000 feet, but much of the Sheep Mountain’s spine is over 9,000 feet, with several peaks slightly under 10,000 feet. At its highest elevations it supports a small bristlecone pine forest (these pines are known to live for several millennia, some as old as 4,000 years). Although there are no running creeks outside of the Corn Creek area, the Sheep Mountains are dotted with springs, over 30 of which have been improved with wildlife guzzlers that greatly extend the range of the desert bighorn sheep as well as many other mammals and birds.

In fact, it was the desert bighorn sheep that first brought me to Corn Creek in the late 1970s (see next two photos). At that time, the US Fish and Wildlife Service trapped several sheep for study, keeping them in enclosures around the Corn Creek Field Office. One of those pens contained Spots, an old ram that passed sometime in the 1980s. They are remarkable animals, and the DNWR is their greatest sanctuary where they are sometimes trapped and relocated to other arid western ranges where populations have declined or been eliminated.

The present-day estimate of the bighorn population in the DNWR is about 750. The current long-term drought has not been kind to them. They are smaller than you might imagine, averaging about three feet tall at the shoulder and weighing about 120 pounds (naturally the rams are larger than the ewes, the biggest of which can weigh as much at 185 pounds). They can last as long as eight days without water, losing about 30 percent of their body weight due to dehydration. But they can drink about 5 gallons of water at one time to replenish what they lost. Both sexes have permanent horns, but only the males sport the large, curled horns that weigh as much as 30 pounds and curl as much as 40 inches along the outside edge of the horn. Just like other bighorn species, the males use their horns to ram into each other in non-fatal fights for mating rights with the ewes during the late summer breeding season.

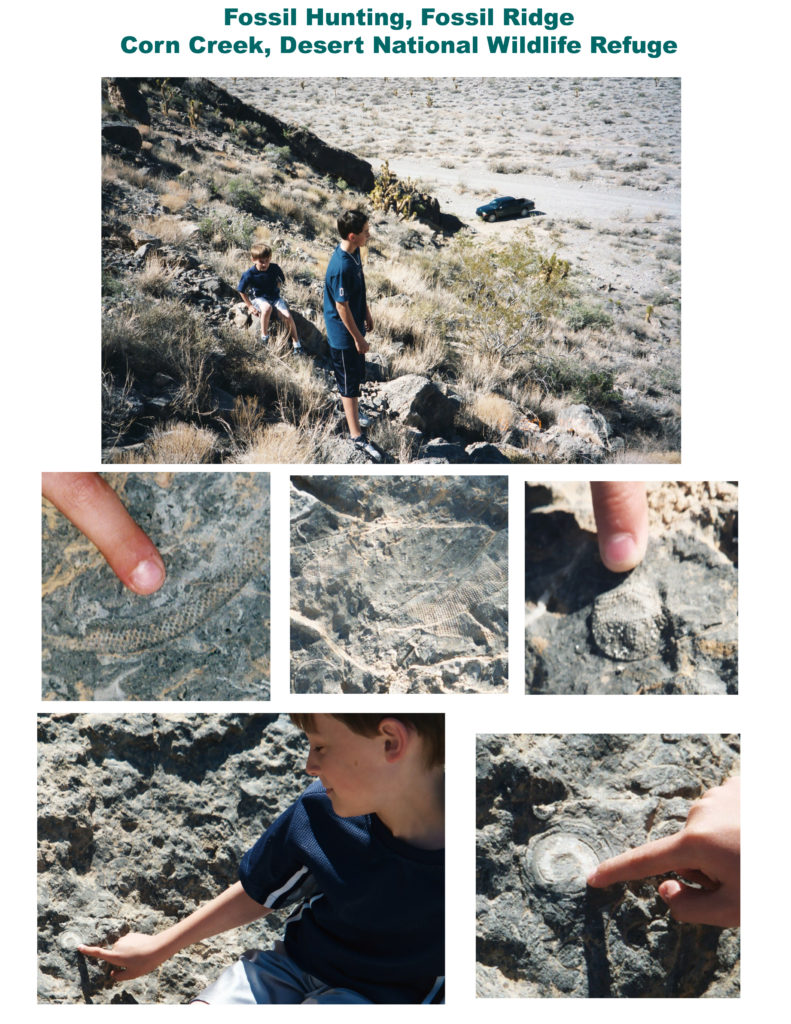

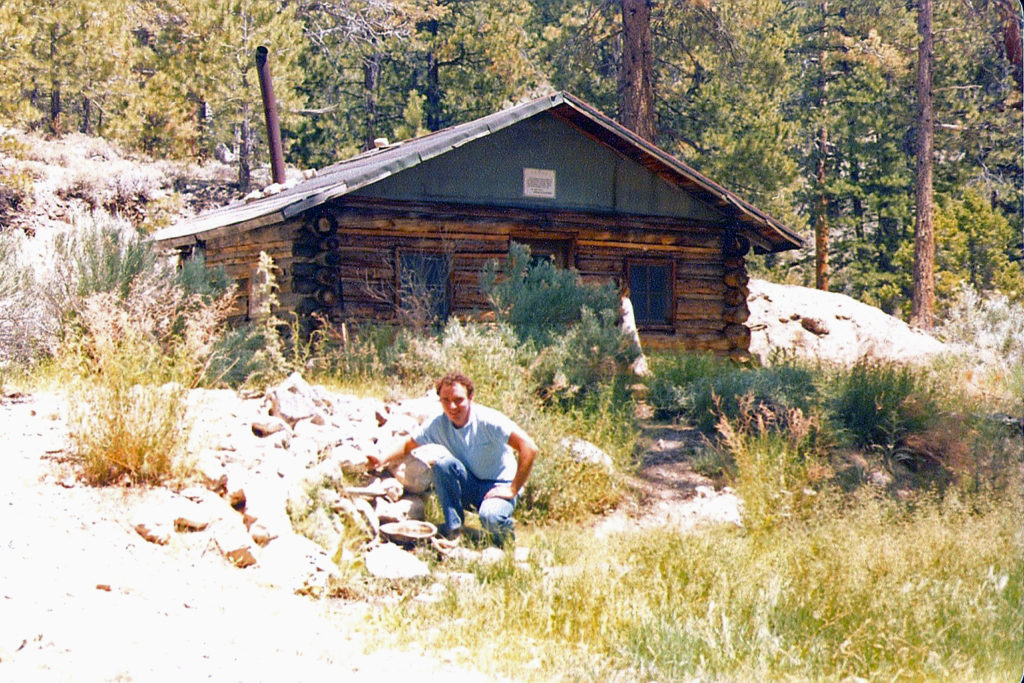

Over the past 40-plus years I have visited Corn Creek numerous times, hiked to the Hidden Forrest cabin once and cross-country skied its canyon another time that roused a ewe from her Deadman Canyon snow bed. This trip with Brian was my third tour of the complete Mormon Well Road all the way from Corn Creek to the Sawmill Canyon trail that links to U.S. Highway 93. I have rarely, if ever, seen other travelers and hikers. This morning when we started up from Corn Creek we saw one vehicle a few miles ahead of us, but once we got to Fossil Ridge we never saw them again, nor anyone else.

Within the DNWR, the ecosystems of the Mojave Dessert and the Great Basin merge, and the history of the people who lived and worked here is quite interesting. In addition to the flora and fauna, artifacts can be found in the DNWR, but usually only by hiking or horseback (Note: it is against the law to destroy or remove these artifacts in the DNWR). The adventuresome can find rock shelters, camp sites, agave roasting pits, petroglyphs, pictographs, and other artifacts.

The DNWR says evidence indicates the people of the Archaic Period lived here, likely in the Late Archaic Period from 2.000 B.C. to A.D. 500. They were known as generalists, which probably explains how they survived the arid Southwest. The Archaic people eventually gave way to the Southern Paiute people. The Europeans, specifically the Spanish pioneers, were the first to encounter the Paiutes in the late 1700s. The Spanish were searching for travel routes between the territories now known as New Mexico and California (the route eventually came to be known as the Old Spanish Trail). By the 1850s the Mormon settlers started to arrive in the valley now known as Las Vegas, and thus the Mormon Well Road got its name. By the turn of the 19th century, two wagon trails were developed: the Alamo Road on the west side of the Sheep Mountains and the Mormon Well Road on the east side of the mountain range. These roads served ranchers and prospectors traveling between the valleys of Pahranagat and Las Vegas. Wheeling on these roads will give you a sense of awe and admiration for the effort and perseverance that was needed to live, work, and survive on these lands.

As pleasurable as this tour through the DNWR was, the best part was spending the day with Brian. I suppose our relationship will always remain father-son, but when your children become high functioning adults and you are waning into your golden years, you naturally become more equal. I might have greater experiential knowledge because of my age, but I mostly find while they might think it interesting, they are more absorbed with their own exploration than my personal experiences, and I have come to respect that. I am always happy to give my advice and opinion, but I have learned to bite my tongue until I am asked. Even then I have learned not to expect my sage advice will contribute to any successful action, at least not the first or even the second time around.

I grew up without a father, but I did have older brothers and mentors who sometimes filled that gap. Mostly I think I learned from my own mistakes and successes, but more often from my failures. Most parents want to help their children avoid their mistakes, and most children want to learn on their own. I get that, it is the natural way. But every now and then one of my sons asks for advice, sometimes indirectly, and later on I might be made aware that they acted upon that advice and were pleased with the results.

As we move more towards equal ground, I find the passing of knowledge and experiences is not as important as being present with them to sympathize, and more importantly empathize with them when they are struggling with an issue. My sons are smart, and fully capable of making their own decisions. Sometimes all they want is their dad to listen and care, to love them where they are without judgment or correction. I pray that I do that in a way that demonstrates my great love for each of them.

Start children off on the way they should go, and even when they are old they will not turn from it.

Proverbs 22:6

Mark,

Another wonderfully informative, thoughtful, and soulful blog. I especially appreciated your wise counsel on being a safe harbor for our adult children, rather than teacher and judge.

It’s healthy and wise to gracefully surrender the things of our youth and embrace the gift of years with gentleness and grace.

Thanks again for inspiring me with your words.

Randy,

Thank you for your comment. You are my faithful brother in Christ in whom I have been blessed.

Sometimes I learn these lessons stubbornly. Like my walk with our Lord and Savior Jesus, it seems to be a process of sanctification where my impurities are burned off over time.

May our Lord continue to give you His peace.

Kelli and I love what you do! Don’t stop! Where did you catch that monster trout?

Thank you Steve.

I assume you are referring the the rainbow I’m holding in the blog’s banner, yes?

You will recall the October 2012 Nevada League of Cities meeting in the city of Elko when I drove up early to fish Illipah Reservoir, the Ruby Marsh Ditch, and the beaver ponds on Lamoille Creek. I returned in May 2015 to fish several waters in Elko County, and the Ruby Marsh Ditch was very good to me. You can read and see more in that post:

Elko County Waters: Ruby Marshes, South Fork Reservoir, and Wild Horse Reservoir.

If you missed that one I think you’ll like the read.

Best to you and Kelli!